Optimizing the Supply Chain, the Avenues Offered for a Full Cost Approach

At the forefront since 2008, the automotive sector has very quickly been forced to adapt and work on the flexibility of its model in order to maintain robust economic performance. To reduce the costs linked to the Supply Chain, once the traditional levers have been activated (supplier negotiations, optimization of transport schemes, reduction of stocks, etc.), manufacturers have decided to go further by making progress on the concept of full cost.

Good Practices for the Deployment of a Full Cost Optimization Approach

The primary purpose of the full cost approach is to orient decision-making processes towards solutions that make it possible to achieve an overall optimum in the Supply Chain. Because of this systemic nature – as opposed to compartmentalized approaches by function – full cost is a fundamental concept of Supply Chain Management.

It is calculated by calculating the sum of the costs borne directly or indirectly by each function up to the service of the end customer.

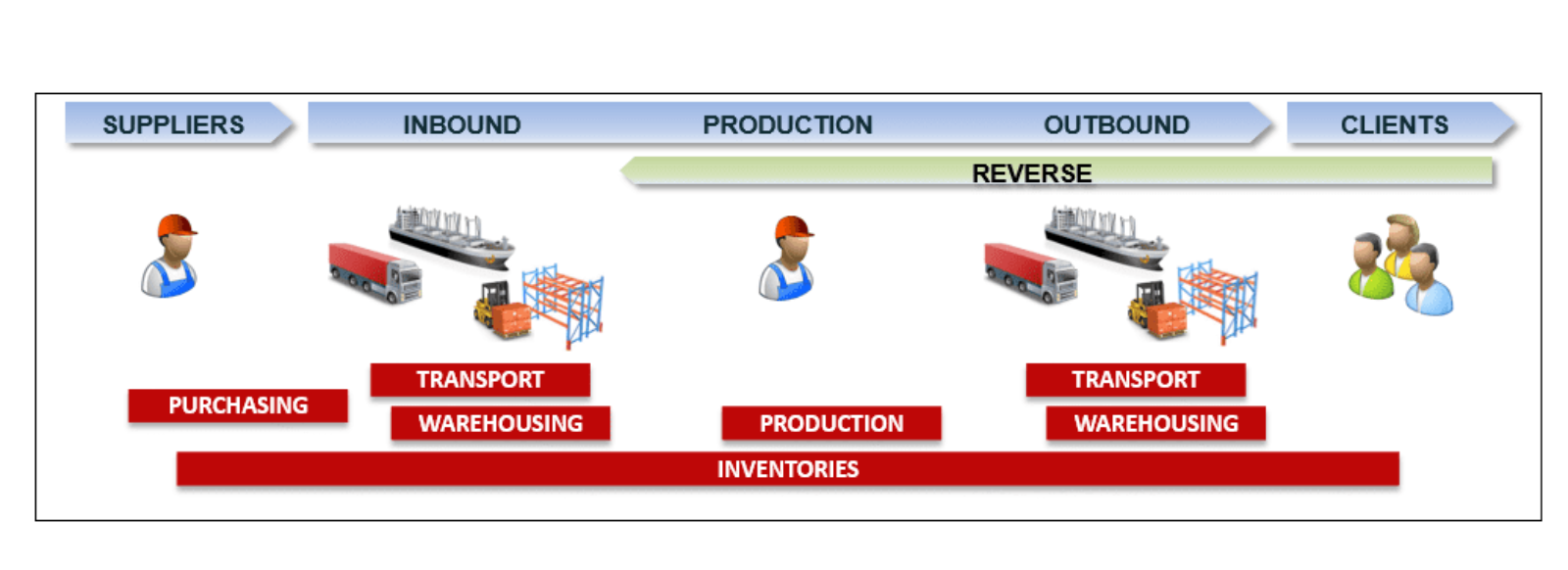

Diagram 1 / Simplified Representation of the Supply Chain With Cost Source and Function

The objective at this stage is to have the most exhaustive possible vision of the costs during its construction in order to measure the impacts – including those usually hidden – of a decision on all the functions of the chain.

In sectors where the value chain is shaped by large long-term programs – vehicle programs in the case of automobiles – this approach is used in particular in order to optimize the models in place during the production life. The full cost must make it possible to pursue disruptive ideas by neglecting the impacts on the cost of a function if the overall result is beneficial.

In shorter-cycle sectors – Consumer Products, various industries – the approach is mainly used for:

- Build the right model when starting production by supporting Make or Buy arbitrations,

- Facilitate and optimize allocation decisions between logistics flow diagrams for each new product launch.

The recurring examples

En construisant la structure de coût de la Supply Chain automobile, on s’aperçoit rapidement que le poids de la partie amont, majoritairement constituée des transports depuis les fournisseurs vers les usines, est conséquent (environ 40% des coûts logistiques totaux). Principal levier de réduction des coûts, l’amélioration du taux de remplissage des camions ou containers nécessite la mise en œuvre de réflexions transverses du type coût complet afin de permettre l’émergence des solutions qui sont en rupture avec les modèles en place :

By building the cost structure of the automotive supply chain, we quickly realize that the weight of the upstream part, mainly consisting of transport from suppliers to factories, is substantial (around 40% of total logistics costs). The main lever for reducing costs, improving the filling rate of trucks or containers requires the implementation of transversal reflections of the full cost type in order to allow the emergence of solutions that break with the models in place:

Supply – Transport Arbitration

Car manufacturers have all gone very far in terms of lot size in their various applications of Toyota’s precepts (cf. the concept of One Piece Flow). However, small batches have a double negative effect. On the one hand, they no longer allow loading optimization (cost / m³ penalized as a result). On the other hand, they contribute to the increase in frequencies and therefore to the multiplication of journeys. The positive impact on the stock levels of the production units is here erased by the additional costs borne by the transport function.

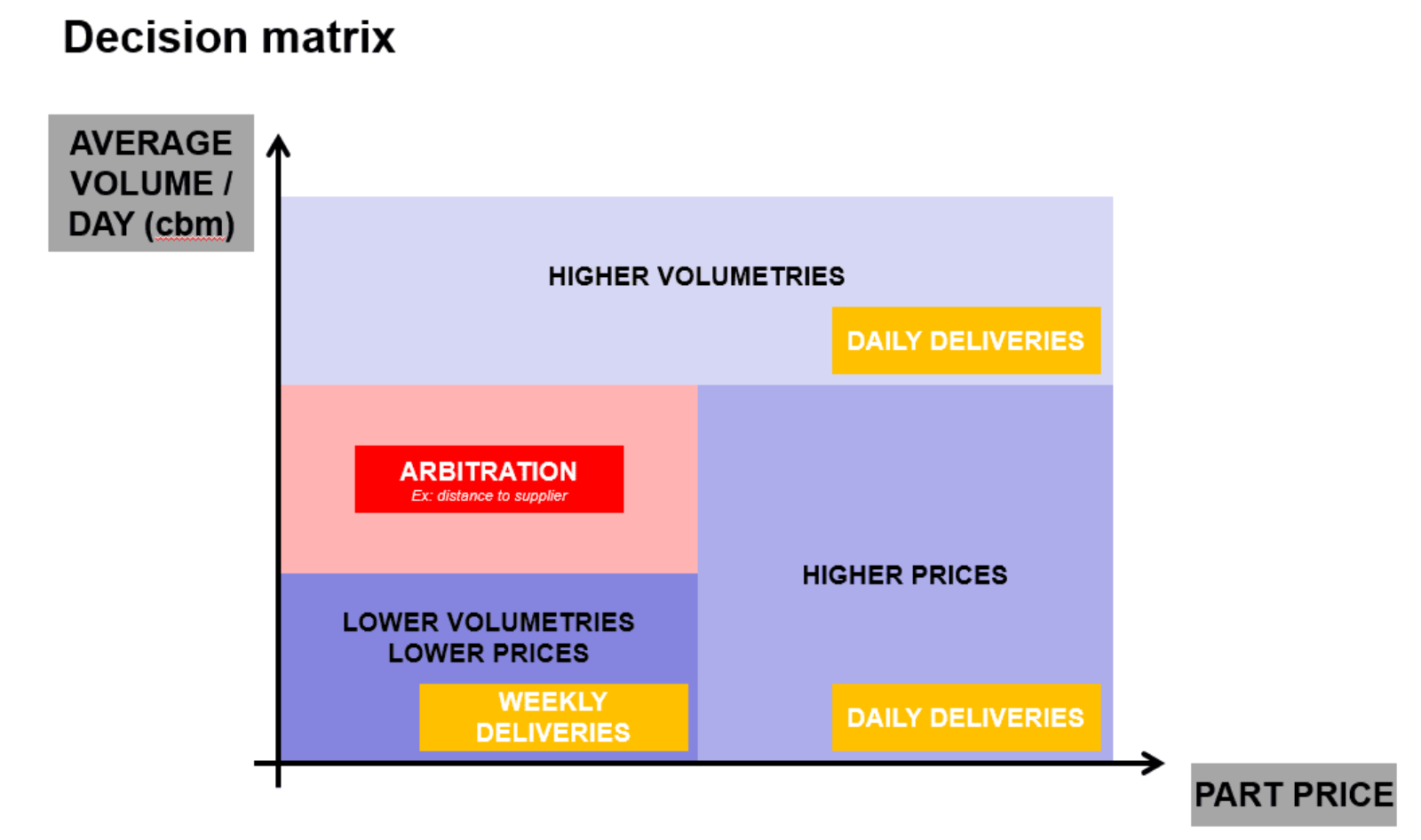

In this case, using the full cost makes it possible to dissociate:

- High-value parts that must be delivered on a daily basis in order to minimize their weight in the inventory (this gain covering the additional transport cost involved)

- The other parts that will be massified in transport at reduced frequencies (weekly if possible) in order to optimize loading rates, the gains in this situation largely covering the differential on the cost of the stock.

Part Design – Transport Arbitration (Design to Logistics)

Still too little measured concretely in the industrial world but clearly identified at the operational level, the impact of the design phase on logistics processes is an important subject to sift through the full cost. Steering columns or exhaust lines are examples of automotive use. For parts combining size and complexity of design, the question of cutting into sub-components – inducing pre-assembly in-house – must be systematically raised on the basis of the various costs to be borne.

This makes it possible to dissociate:

- Parts which make a fairly short journey in terms of km and / or which require a very complex assembly process or even not mastered internally, these parts having to be supplied by finished assemblies,

- Parts that are expensive in transport – depending on the km traveled and the volumes packed – and for which the cost of pre-assembly in-house is competitive, these parts having to be broken down into sub-assemblies during the design.

The idea of such a division is to be able to densify the parts within the same packaging and consequently to improve the cost / m³ ratio of goods transported – up to 30% in the context of the steering columns. or exhaust lines.

Avenues for Implementation Outside the Auto Sector

In sectors other than Automotive, the simplified representation of the Supply Chain with cost source and function can be done around trade-offs between Marketing and Logistics, for example.

In distribution, the full cost analysis of the use of ready-to-sell packaging on low-cost ranges is not yet very widespread, although it draws some interesting conclusions. These packaging, originally planned to reduce shelf-time, are very unstable to handle during all the upstream stages and suffer from a markdown rate 4 to 5 times higher than in warehouses, thus penalizing the final cost. returned to the client. Conversely, on premium ranges for which the packaging is designed to be resistant, ready-to-sell products can generate real savings and improve the customer experience.

The keys to Implementation

The transversality of the approach and the need to decide on an overall optimum that breaks with the established scheme necessarily induces friction between businesses that still function too closely in a logic of silos.

Here are the main principles that the manufacturers have adopted to complete the process:

# 1 Make Dashboards Consistent

The creation of a global full cost objective common to the different functions and the alignment of the objectives of each limit the blockages related to divergent indicators and reduce the areas of tension.

# 2 Adapt the Organization

The establishment of a unit to manage the full cost subject at general management level and the appointment of referents in each business is an essential condition to guarantee effective project animation. The latter should promote the identification and implementation of concrete opportunities existing in the Supply Chain.

# 3 Define an Arbitration Body

The appointment of a top manager with final decision-making power in the event of a blockage avoids having to constantly resort to the management committee to decide. This decision-making power can even be given to the plant manager who is no longer just in charge of his productivity but rather of the entire value chain of his vehicle.

# 4 Develop the Supply Chain Maturity of Actors

It is the basis of the work, training and communication allow operational staff to understand the meaning given to the use of the full cost tool.

The Right Reflexes

Moving forward on full cost issues requires the ability to compile a large amount of data in a structured manner and then exploit it in order to provoke trade-offs. For this it is necessary to:

# 1 Structure Cost Models

While a good knowledge of all the applicable costs for each process is a good starting point, the goal must be quickly to structure generic cost models that reflect the various existing options and the associated full cost. This point has already been developed by manufacturers but is also found in sectors such as large-scale distribution under the name of rating tables.

These make it possible to make the choices of logistics diagrams by comparing different possible scenarios. The first step in this case is to frame the potential channels – import, domestic stored, domestic cross dock, domestic direct for example – and the processes that they involve.

The Supply Chain function records the costs of each stage in parallel in the grid, paying particular attention to the processes whose criticality and / or recurrence are known in advance. Typical example: what is the real cost of not palletizing goods on import flows?

The purpose of such a grid is to be able to automate and optimize the allocation of each new product in such and such a sector according to the cost delivered to the customer.

# 2 Facilitate Arbitration

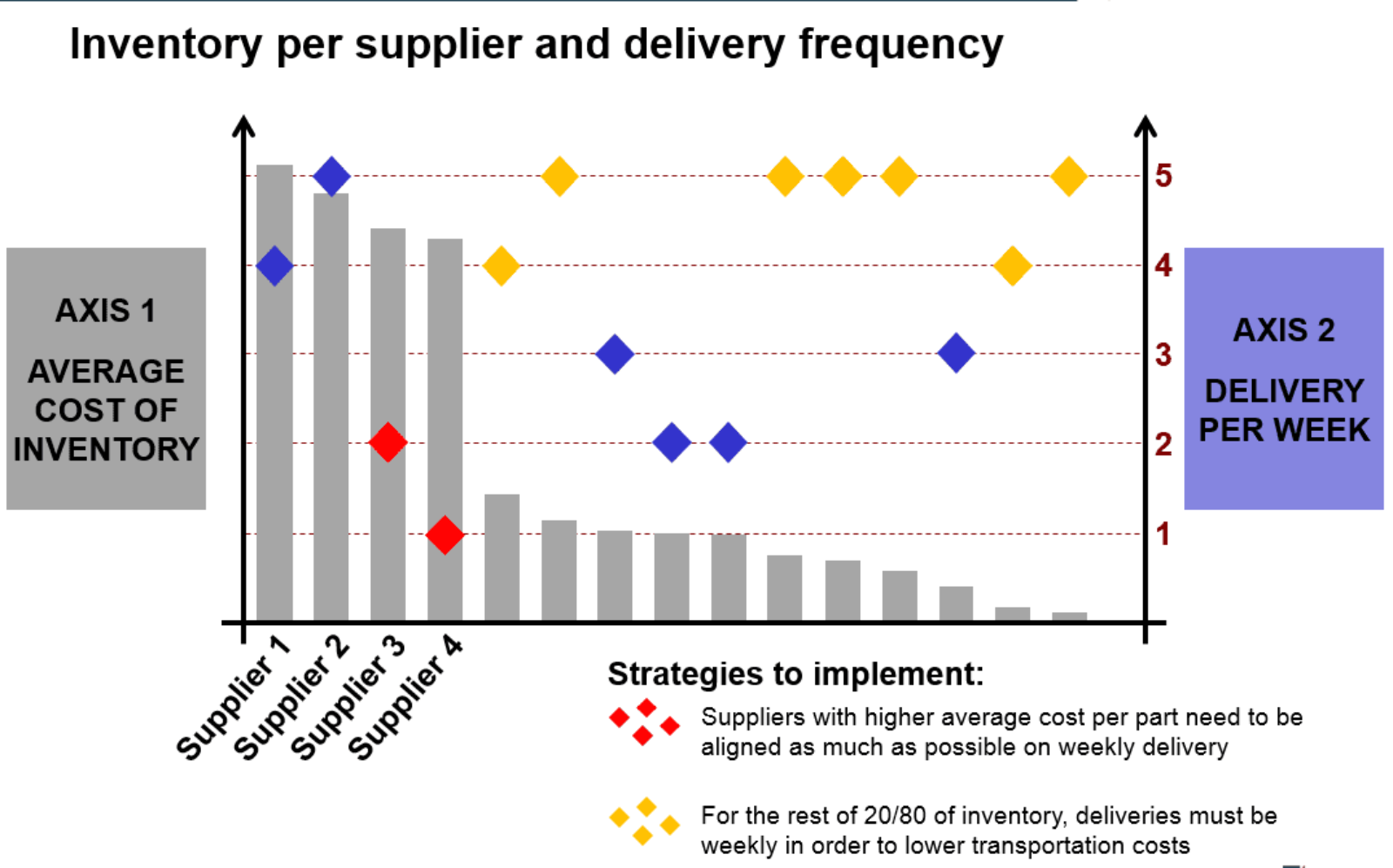

Extracting key data and presenting it in synthetic form is the best way to build buy-in around a change scenario. On the issues of lot size in the automotive sector, a synthetic view of stocks by supplier and the delivery frequencies used is a good example of the current situation bringing together the production and transport businesses.

Figure 2 / Inventory vs Frequency Graph

In the rest of the arbitration process, the use of decision matrices makes it possible to clearly share and then validate the main rules to be used to review management methods.

Diagram 3 / Delivery volume vs part value matrix

In the automotive sector, the introduction of this approach has already proven its worth by significantly reducing upstream logistics costs and thus improving the operating margin. It makes it possible to put on the table innovative cost reduction scenarios by basing the final arbitration on the overall gain generated for the manufacturer.

In conclusion

The full-cost approach is starting to be deployed in other industrial sectors (than Automotive) and in certain parts of the distribution sector, with real opportunities at stake.

It requires putting in place robust tools, adopting new management systems and finally driving change within the company through targeted training and communication actions.

For this, the approach must be the subject of a business plan led by a dedicated team and supported by General Management.