5 Good Practices to Better Pilot Your Distribution Costs and Boost Your Range Strategies

Best Practice # 1: Better Understand Your Operational Costs

This need is all the more current as the “customer-centric” approaches developed in recent years have considerably complicated operations among manufacturers and distributors. Foremost among the constraints weighing on the Supply Chain is the issue of ultra-responsiveness.

For example, the frequency of deliveries to customers has increased fourfold over the past 10 years among players in the dry food industry. At the origin of this trend are distributors concerned with keeping their inventory levels as low as possible.

This splitting of orders generates obvious additional costs, of transport obviously, but also of management and preparation of the orders. However, these additional costs are too rarely quantified precisely by manufacturers and therefore difficult to pass on to partners down the value chain.

The financial approach consolidated in the operating account very often masks critical and very heterogeneous operational realities. An analysis at the customer level and product families is then necessary.

We Recommend a Two-Step Operating Mode:

Step 1: Flow Mapping

Carry out a mapping of physical flows and information flows, type VSM (“Value Stream Mapping”) to have a complete view of the different operations, from the issuance of the customer’s requirement to the delivery of the latter, starting from the general case to then describe the specifics and particularities.

Step 2: A Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Logistics Operations

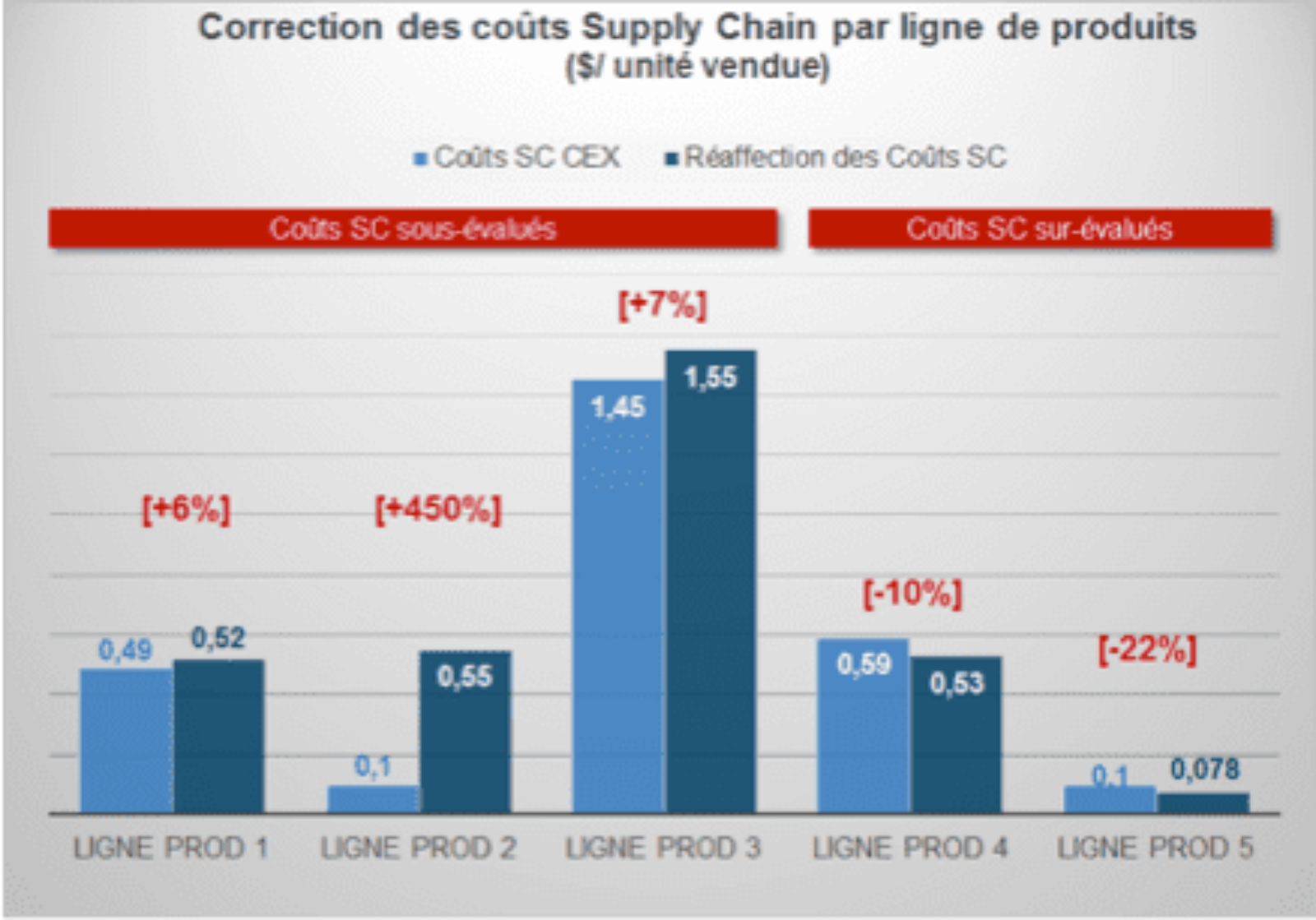

Analyze and observe the flow lines in detail, in the field, to qualify and quantify the logistics operations associated with each customer. During these field surveys, it is not uncommon to notice that the distribution cost of the same product can vary from one to three depending on customer requirements … and, through this, significantly distort the rate of margin calculated on a product segment.

Two main categories of costs can generate profitability differences:

- Operations: packaging, control, retail picking, specific loading, markdown rate, etc.

- The organization and management process associated with the customer: forecasts, after-sales service, animation of ranges and promotions, …

It is then a matter of reallocating operational and administrative costs as accurately as possible, depending on the effective mobilization of your organization for each of these customers.

Best Practice # 2: Challenge your SEO

Are You Sure That Your Marketing Teams Know the Real Costs of Distribution to Your Customers?

It is a safe bet that the cost mapping step (BP # 1) will give new momentum to your range strategy analyzes. What to do with customers not generating satisfactory profitability? The first reflex, which would consist in re-evaluating selling prices upwards, is rarely sustainable from a commercial point of view.

It therefore remains to optimize these Supply Chain costs, by working on the massification of logistics operations. This involves carrying out a detailed analysis of the “product mix” by customer to ensure that each customer’s basket contains a minimum of low-profit references.

We Recommend 2 Axes to Initiate This Approach

1 / Approach From the Bottom of the Basket

This involves studying the margin achieved by each item and comparing it with the recalculated Supply Chain costs to validate or not its maintenance in your offer. The support of this pragmatic and robust cost estimate allows the internal alignment of teams and objective the range review process.

This analysis, carried out at an FMCG manufacturer, revealed that 8% of the items in its shelf base had, over the past 12 months, a distribution cost greater than the margin they generated.

2 / Approach From the Top of the Basket

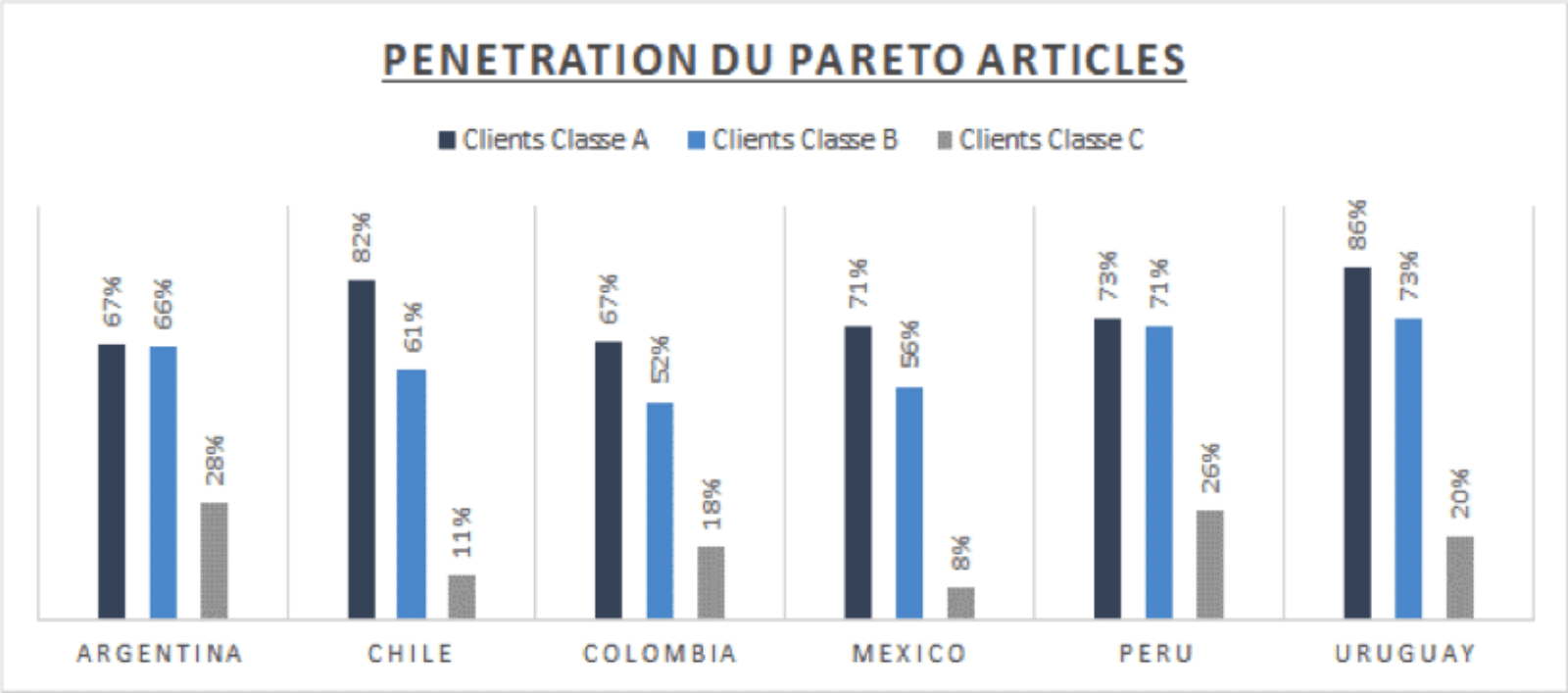

This is to identify the penetration rate of your 20/80 with your class A, B and C customers.

This analysis makes it possible to bring out the accounts with exclusive references maintained in range or even developed, whereas Pareto references could meet the need. Final objective: to work on the massification of the article base.

In the example below, for one of our customers in the FMCG, we were able to offer, in 20% of cases, alternative references that perfectly met the customer’s needs. Specific or even single-customer products have thus been able to be partly replaced by references from 20/80 and thereby removed from the catalog.

Good Practice # 3: Sharing Information

A customer cannot guess the real loss of productivity that a request from him generates on your business … it’s up to you to bring the matter up.

Some good reflexes to acquire:

Share With Your Customers the Operations Associated With Their Specific Request

Give them visibility into your costs, especially when they work in increments and not in a linear fashion. Remember, it is impossible for a client to “guess” your threshold effects. You will then be able to work with them on min / max parameters that they will be better able to understand and therefore accept.

Define the Rules Internally

For example, are you sure you want to provide the “at any cost” rate of service? What is the marginal logistical cost of this last minute order? Re-prioritization, truck shift, arbitration meeting… Too often we find that the process of defining ATP (Available-To-Promise) is not clearly defined… or, if it is formalized, that it is not respected on a daily basis.

Arbitrate Based on Concrete Figures

The logic of a differentiated supply chain too often consists of providing better service to large customers. What if, on the contrary, you place the cursor not according to the client’s weight but to what he earns you? It is much more legitimate to provide a higher level of logistics service to a very profitable customer, rather than to large customers for whom there may be more limited room for maneuver.

Good Practice # 4: Harmonize and Standardize Your Logistics Operations

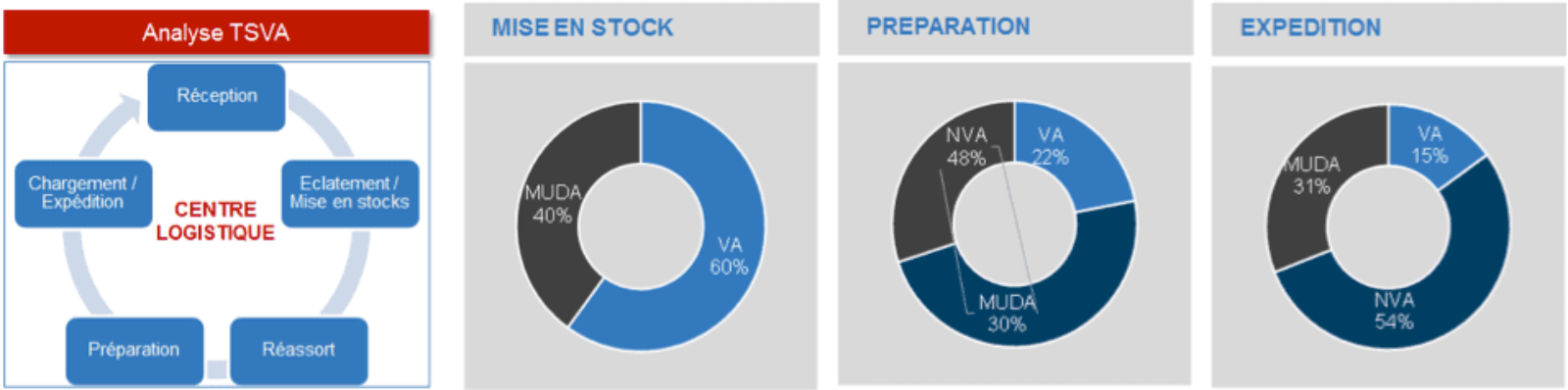

Do You Control the Variability of Your Operations and Your Productivity Gaps?

This question can quickly become a real headache when entering picking operations, with very varied customer types. The challenge then is to develop benchmarks and harmonize practices around standards. It’s about applying Lean Manufacturing practices to your logistics operations. The hunt for MUDAS allows the realization of significant productivity gains in logistics centers as well as the rapid implementation of the first improvements.

In non-automated centers carrying out picking, experience shows that on average 30% of the actions carried out by operators and foremen are pure waste. The implementation of an improvement plan makes it possible to reduce this waste by 10 to 15%, ie as many points gained in your operating margin.

Three Major Levers Are Used in the Implementation of These Improvement Plans

Tools and Processes

- Implementation of standards defined with the teams,

- Revision of the ground plan of the logistics center and its equipment.

The Organization

- Review of the thread of the day,

- Decompartmentalization of operations and professions, …

Management Systems

- Animation of the performance,

- Cascade of objectives,

- REX and improvement loop.

Best Practice # 5: Changing the Negotiation Paradigm

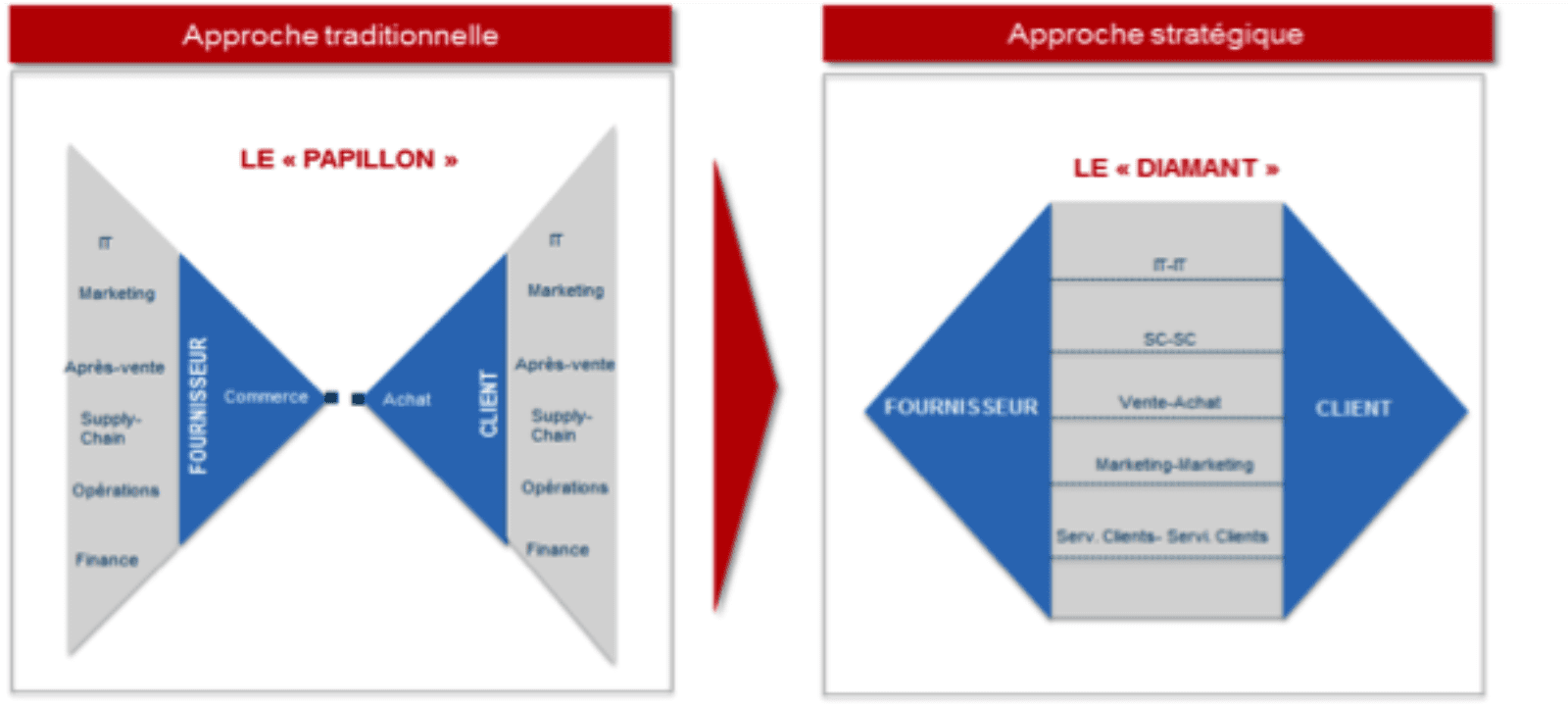

It is Still Too Rare to See Customer-Supplier Supply Chains Talking to Each Other Directly.

However, your Sales and Purchasing departments do not have all the cards in hand to create an optimal transversal Supply Chain.

We have seen the emergence of collaborative initiatives between manufacturers and distributors in recent years. Improvement projects can be summed up in 5 major themes:

- Forecasts,

- Shelf availability,

- Data exchange,

- Supply Management,

- Logistics pooling.

All these working groups, focused on customer service, only partially address the global and cross-functional cost issues of the Supply Chain *.

We very often have the opportunity to support our customers, manufacturers or distributors, in their optimization process and the observation is relatively simple: the notion of transversal Supply Chain remains an abstract concept, each one struggling to optimize its logistics costs, sometimes to the detriment of overall performance. This requires developing the notion of strategic alliance and modifying the traditional approach of the buyer-supplier supply chain.

The Most Exploited Industrial-Distributor Logistics Optimization Axes

Reflection on the Control of Transport (Incoterm)

- “Carriage paid”, making it possible to work on batch optimization and obtain economies of scale;

- “Ex-works”, thus giving the distributor the possibility of optimizing costs – if they have the right conditions – while avoiding MOQ (Minimum Order Quantity)

Review of Supply Chains

- Stocked flow,

- Cross-dock,

- Short / local distribution network.

A complete understanding of Supply Chain costs, “beyond the wall”, will open up many avenues for optimization. For that, it requires getting the business people to talk to each other to redefine the right needs with regard to the impact on distribution costs.

In a difficult economic context, where negotiations between manufacturers and distributors are increasingly tense, it is urgent to change the paradigm and open up the horizon for negotiations. The most interesting sources of cost optimization lie in collaborative Supply Chain approaches.

Conclusion

In this race for customer service, it is essential to manage your distribution costs in order to survive.

Modeling these costs is an essential decision support tool for making the right decisions in an agile manner. Our clients favor this “Cost-to-Serve” approach with 3 main challenges for their business:

- Understand the real profits generated by product line and by customer

- Identify cost optimization avenues for their transversal Supply Chain

- Simulate the impacts of potential changes to their models and adjust their Supply Chain accordingly

*Source : ECR (Effective Consumer Response)